Description of Padartha.

The term “Padartha” is formed by merging two words: “Pad” and “Artha,” where “Pad” signifies a linguistic unit in Sanskrit grammar that conveys meaning and can function independently. According to Panini’s grammar, “Pad” can be categorized into two primary types:

- “Subanta”: These are nouns or names that remain unchanged and do not undergo inflection. They typically denote people, objects, places, and concepts. For instance, “Rajesh” and “Mahesh” are examples of Subanta words.

- “Tidanta”: These are verbs that undergo inflection based on tense, gender, number, and person. Tidanta words denote actions or events. For instance, “Dhawti” (jumps) and “khadati” (eats) are Tidanta words.

Therefore, the essence of “Pad” lies in its representation of both entity and action.

In the Charaka Samhita, specifically within the Sharira Sthana, “Artha” signifies various tangible entities apprehended by the senses. These entities encompass:

- Shabda (sound): Representing auditory experiences or the faculty of hearing.

- Sparsha (touch): Signifying tactile perceptions or the sense of touch.

- Rupa (vision): Indicating visual perceptions or the faculty of sight.

- Rasa (taste): Concerning gustatory experiences or the faculty of taste.

- Gandha (smell): Denoting olfactory perceptions or the faculty of smell.

Significance of Padartha

Within Ayurveda, Padartha encompasses not solely physical entities but also delves into the metaphysical dimensions of existence.

Rooted deeply in Indian philosophy, the concept of Padartha serves as a foundational element for grasping the principles of Ayurveda. It offers a structured approach for classifying and comprehending diverse components of the cosmos, spanning humans, substances, attributes, activities, and connections.

Through the exploration of Padartha’s multifaceted essence, scholars of Ayurveda have unraveled the complexities surrounding health, illness, and holistic wellness.

Characteristics of Padartha

Within Indian philosophy, “Padartha” is characterized by three fundamental attributes:

- Astitvam (Existence): Padartha encompasses entities that hold genuine existence within the realm. These entities manifest tangibly, such as physical entities like trees, animals, and humans, as well as intangibly, such as abstract concepts, emotions, and qualities.

- Jneyatvam (Knowability): Padartha denotes entities that are knowable, understandable, and graspable. They serve as subjects of cognition and can be comprehended through various means, including perception, inference, and testimony.

- Abhidheyatva (Denotability): Padartha signifies or denotes objects through linguistic expressions. Language serves as a vital tool for articulating and communicating the essence, attributes, and interconnections of these entities. The terminology employed to elucidate Padarthas plays a pivotal role in conveying their significance and facilitating effective communication.

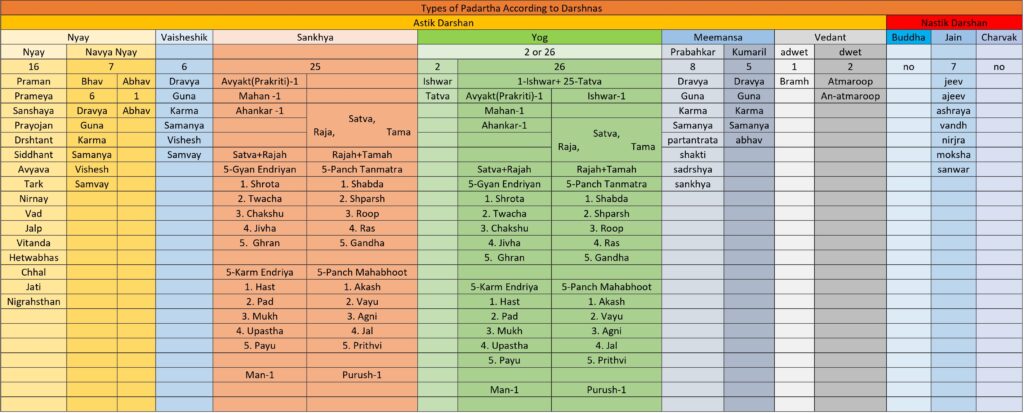

Types of Padartha according to Darshnas

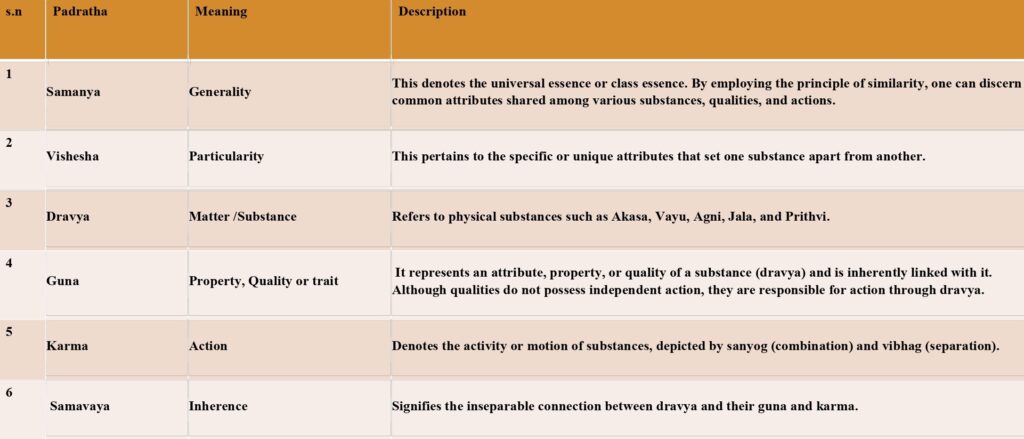

Bhav Padartha(Six ontological categories of an object)

Abhav Padartha (Non-Existence)

The concept of non-existence as the seventh category of Vaisesika substance does not find mention in Kanada’s original teachings. Instead, it was later introduced by his commentators. According to Vaisesika philosophy, non-existence, like existence, is perceivable. It denotes the absence of an object. For instance, one cannot refute the absence of the sun behind the dark clouds on a rainy day. Therefore, it holds a crucial place in the Vaisesika system.

Non-existence is broadly classified into two types:

- A. Sansargabhava

- B. Anyonyabhava

A. Sansargabhava

signifies the absence of one entity within another, represented symbolically as ‘X is not in Y.’ Examples include the absence of coolness in fire or squareness in a circle.

Sansargabhava further divides into three kinds:

- (i) Pragbhava or antecedent non-existence

- (ii) Dhvansabhava or subsequent non-existence

- (iii) Atyantabhava or absolute non-existence

A. (i). Prāgbhāva

Pragbhava denotes the absence of a substance before its production or creation. For instance, a chair does not exist before the carpenter crafts it, implying that prior to its creation, the chair’s non-existence resides in the wood. Similarly, the absence of a pot in clay before it’s shaped into one. Antecedent non-existence lacks a beginning but possesses an end.

A.(ii). Dhvansābvhāva

Dhvansabhava represents the absence of a substance after its destruction. For example, the absence of a pot once it’s shattered. Despite its destruction, a pot can be remade from its pieces. Hence, subsequent non-existence initiates but doesn’t conclude.

A.(iii). Atyantabhāva

Atyantabhava signifies the perpetual absence of one thing within another across all times—past, present, and future. For instance, the absence of heat in the moon. Absolute non-existence transcends both origin and cessation. It’s eternal; for instance, the absence of color in space persists indefinitely. Absolute non-existence neither begins nor ends—it simply is.

B. Anyonyabhāva

Anyonyabhava, also known as mutual non-existence, denotes the exclusion of one thing by another. It signifies the absence of something within another object, expressed as ‘X is not Y.’ For instance, a table is not a horse. The absence of a table within a horse and vice versa illustrates mutual non-existence. Anyonyabhava is eternal because disparate entities perpetually exclude each other under all conditions.

Avyakta or Prakriti(Karan)Padartha

According to Sankhya Philosophy “Karan” is only one “Prakriti”.

Prakriti precedes creation. It is ancient, eternal, omnipresent, unchanging, unparalleled, without origin, and uncaused. Prakriti stands as the solitary and self-sufficient origin of the Universe. If there is any dependency within Prakriti, it resides within its inherent nature characterized by the three gunas. Through these gunas, Prakriti orchestrates creations guided by Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas. The interplay of these three gunas forms a symbiotic relationship.

According to Sharangdhar synonyms of Prakriti are Pradhan, Shakti, Nitya, Avikriti.

In Indian philosophy, the concept of Karan, or cause, is pivotal. Karan is the factor preceding Karya, the effect, and is essential for its occurrence. It is the antecedent element that inevitably leads to a subsequent effect. However, not every antecedent factor qualifies as Karan;

It must meet three criteria:

- Purva vritti (Temporal precedence): The cause must exist before the effect.

- Niyat (Invariable connection): Wherever the effect is present, the cause must also be present consistently.

- Ananyathasiddh (Indispensability): The effect cannot materialize without the cause.

Karan manifests in three distinct types according to Nyaya Philosophy:

- Samavayi Karan (Inherent Cause): This type of cause is so intimately intertwined with the effect that they are inseparable. The effect’s existence relies entirely on its connection to the Samavayi Karan, also known as Upadana Karan.

- Asamavayi Karan (Non-Inherent Cause): Unlike Samavayi Karana, Asamavayi Karan is not inherently linked to the effect but coexists with it within the same object. Though distinct from Samavayi Karan, it is closely associated with it.

- Nimitta Karan (Instrumental Cause): This category encompasses all other essential causes apart from Samavayi and Asamavayi Karanas. Nimitta Karan plays a facilitating role in the production of Karya but detaches from it after creation. It complements Samavayi and Asamavayi Karanas indirectly, enhancing their effectiveness.

Vikriti(Karya) Padartha

According to Sankhya Philosophy Karya or Vikriti are 16 in numbers in two main divisions

Ekadash Endriyan and Panch Mahabhoot are two main divisions.

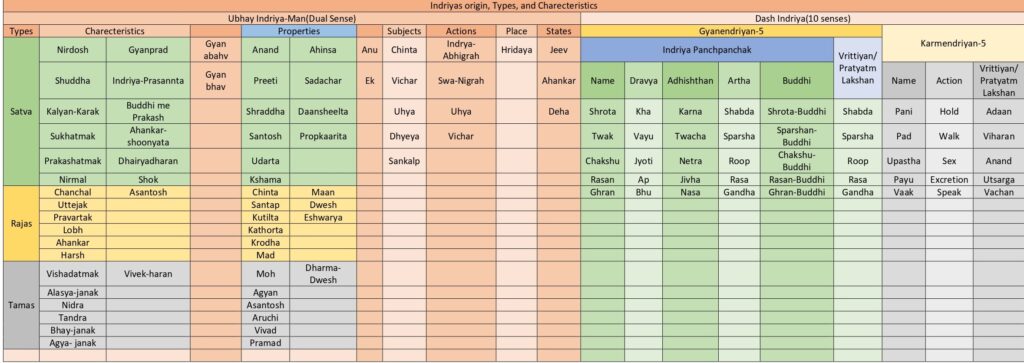

The indriyas consist of the manas (sensory or processing mind), the five karmendriyas (organs of action or senses), and the five gyanendriyas (organs of wisdom or knowing).

The gyanendriyas encompass the lower senses: ears (shotra), eyes (chakshu), nose (grahnu), tongue (jivha), and skin (tvak).

Karmendriyas are the organs through which interaction with the material world occurs. The feet (pada) facilitate movement, the hands (pani) grasp and hold, the rectum (payu) eliminates waste, the genitals (upastha) engage in procreation, and the mouth (vak) articulates speech.

Types of Indriyan:

Panch-Mahabhutas: Vikriti(Karya) Padartha

Mahabhutas Overview:

- The concept encompasses five elements: Akasa, Vayu, Agni, Jala, and Prthivi.

- •Each element is associated with distinct properties: sound, touch, vision, taste, and smell.

- •In Samkhya philosophy, these elements are categorized under sixteen Vikaras.

- •According to Vaiseshika system, the grossness of Bhutas emerges during the Trisarenu stage, where they are referred to as Mahabhutas.

1.Akasa Mahabhuta:

- Characterized by the quality of sound alone.

- Described as a substance abundant in Satva Guna.

- Qualities include softness, lightness, subtlety, and smoothness.

- Contributes to sound, the sense of addition, lightness, subtlety, and distinction in body development.

2.Vayu Mahabhuta:

- Contains an excess of Rajoguna.

- Originates from Akasa and discernible by its Sparsa Guna.

- Charaka Samhita details five types of Vata Dosha.

- Properties include Sparsa, Samkhya, Parimana, Prthaktva, Samyoga, Vibhaga, Paratva, Aparatva, and Samskara.

- Influences qualities such as heat, sharpness, subtleness, lightness, and non-sliminess.

3.Tejasmahabhuta:

- Characterized by luminous nature, rich in Satva and Rajoguna.

- Possesses attributes like Rupa, Sparsa, Samkhya, Parimana, Prthaktva, Samyoga, Vibhaga, Paratva, Aparatva, Dravatva, and Sanskara.

- Influences qualities related to heat, sharpness, subtleness, lightness, non-sliminess, and vision.

4.Agni Mahabhuta & Jala Mahabhuta:

- Agni gives rise to Jala Mahabhuta, abundant in Satva and Tamas Gunas.

- Jala Mahabhuta possesses attributes like Rupa, Rasa, Sneha, Sparsa, Samkhya, Parimana, Prthaktva, Samyoga, Vibhaga, Paratva, Aparatva, Gurutva, Dravatva, and Samskara.

- Medicinally influences taste-related attributes and plays a crucial role in various diseases.

5.Prthivi Mahabhuta:

- Associated with Rupa, Rasa, Sparsa, and Gandha.

- Plays a vital role in bodily formation, shaping, and growth.

- Instrumental in mineral and vegetable kingdoms, used in medical science and dietary materials.

Prakriti- Vikriti Padartha:

Some entities are both primordial matter as well as entities evolved out of it.

Its consists of Mahat Tattva, Ahankar, Panch-Tanmatra.

Upon the onset of Prakruti’s evolution, the initial Mahatattva, Buddhi (Intellect), emerges. Ahankâr, the agent of action, arises from Buddhi. Mind, in turn, shapes Ahankâr, facilitating its functions through the Karmindriyâs (Organs of Action). This process involves experimentation, aimed at both accumulating experiences and executing actions, thereby defining the responsibilities of the Mind.

- Mahattattva, also known as Mahat, is a fundamental principle described in the 10th-century Saurapurāṇa, a Śaivism Upapurāṇa. According to this text, Mahattattva embodies the essence of both pradhāna and puruṣa. It originates from the interplay of disturbed prakṛti and puruṣa, akin to a seed germinating from this cosmic disturbance. Initially enveloped by pradhāna, Mahattattva manifests in three distinct forms: sāttvika, rājasa, and tāmasa-mahat. Like a seed encased in its husk, Mahattattva remains concealed within pradhāna until it differentiates into vaikārika, taijasa, and bhūtādi or tāmasa, representing the threefold ahaṃkāra.

- Ahaṅkāra, literally translated as ‘egoism’, is the force behind abhimāna, the identification with the self and possessions. In Sāṅkhyan metaphysics, which influences Vedānta, ahaṅkāra emerges as the principle of individuation following mahat or buddhi in the evolutionary process from prakṛti (nature). It is viewed as a substance since it serves as the material cause for other entities such as the mind or sense organs. Through its influence, individual selves, or puruṣhas, acquire distinct mental frameworks, identifying with the actions of prakṛiti through ahaṅkāra.

At the individual level, ahaṅkāra shapes the perception of sensations through the senses and mind, and guides decision-making via intellect. On a cosmic scale, ahaṅkāra gives rise to the five senses of cognition (jñānendriyas), the five organs of action (karmendriyas), the mind (manas), and the five subtle elements like earth (tanmātras).

In some Vedāntic texts, ahaṅkāra is depicted as a function of antahkaraṇa (internal instrument or mind), responsible for fostering the ego-sense and possessiveness.

The Pancha Tanmatra, deriving from Sanskrit roots—pancha (five), tan (subtle), and matra (elements)—denote the quintessential perceptions or subtle essences that correspond to the five senses. These elements encompass: rupa (form), gandha (smell), sparsa (touch), rasa (taste), and sabda (sound).

Aligned with the cognitive senses known as Pancha Jnanendriya—caksu (eyes), ghrana (nose), tvak (skin), rasana (tongue), and srotra (ear)—the Pancha Tanmatra represent integral components among the 36 tattvas, or facets of existence, within Saivism.

The Pancha Tanmatra serve as conduits through which we perceive and interact with the external world, embodying the essence of sensory experience. Another interpretation of tanmatra as the “mother of matter” signifies the foundational energy underlying creation itself.

Moreover, the amalgamation of Pancha Tanmatra gives rise to the gross elements constituting the universe:

- The earth element stems from all five Tanmatra.

- The water element arises from sound, touch, sight, and taste.

- The fire element manifests from sound, touch, and sight.

- The air element emerges from sound and touch.

- The ether element originates from sound.

Na-Prakriti- Na-Vikriti Padartha:

Some entities are neither primordial matter nor an entity which has evolved out of primordial matter (Purusha).

Purusha stands aloof, distinct from Prakruti, devoid of commencement or conclusion, bereft of attributes, elusive yet omnipresent. It transcends intellect, mind, and senses, surpassing even the confines of space, time, and agency. As the primordial observer, it remains unblemished and eternal, embodying pure consciousness. Though non-participatory in deeds, it merely witnesses, hence experiencing both joy and sorrow. Analogous to colorless glass revealing the hue beneath, Purusha, detached from Prakruti, becomes entwined upon entering the worldly realm. Referred to as the Witness, Seer, and Liberated in Sânkhya

Scriptures, its entanglement with Prakruti leads to the duality of experience. Through discerning wisdom, it seeks emancipation, aspiring towards Moksha, liberation from the cyclic existence of birth and death. Until then, the wheel of life perpetually ensnares Purusha, reaping the consequences of its actions.

In Ayurvedic texts, the term Purusha encompasses various connotations such as Puman or Nara (Male), Ishvara (God), Jiva (living creatures), Prani (Sentient beings), and Manushya (human beings). Etymologically, Purusha denotes human beings, considered supreme in the evolutionary journey, or the Atma residing within the body, referred to as Puri. However, in its true essence, it signifies the conscious human form.

This Purusha is also known as Karmapurusha, Rashipurusha, Sanyogapurusha, and Lokpurusha. In the realm of medical science, Purusha is regarded as the vessel or focus because it serves as the locus of both ailment and well-being.

Purusha, in these philosophical and medical traditions, is often depicted in different ways, representing the essence of consciousness or the fundamental elements of existence. Here’s a breakdown of the concepts presented:

- Ekdhatuja Purusha: This signifies the Absolute or Pure Purusha. It’s unchangeable, indistinct, and a seat of consciousness. It’s said to reside within the body and manifests in various forms, such as Karma Purusha or Rashi Purusha.

- Shad dhatuj Purusha: This Purusha is composed of six dhatus, including the five Mahabhutas (earth, water, fire, air, and ether) and Jivatma. It’s also associated with factors contributed by the mother, father, soul, mind, and digestive products of the mother’s food in the formation of the embryo.

- Chaturvinshatamaka Purusha: Recognized by Maharishi Charaka and Kashyapa, this Purusha is composed of twenty-four Tattvas or elements. These include the mind, ten Indriyas (sensory and motor organs), five objects of sense organs, and Prakriti consisting of eight Dhatus (subtle forms of the Mahabhutas, ego, intellect, and unmanifested matter).

In addition to Ayurveda, the concept of Purusha is discussed in various Darshanas:

- Sankhya and Yoga Darshan: They discuss the constituents of Purusha, which aligns with the concept of Caturvinshatmaka/Panchvinshatmaka Purusha, including Atma and Mana.

- Vaisheshika and Naya Darshan: These deal with the physical entity and logic, corresponding to the concept of Shad dhatuja Purusha, which includes the Panchmahabhutas and Atma.

- Vedanta and Mimansa: These discuss Vedic rituals and Brahma, reflected in the Ekdhatuja Purusha, focusing on Atma.

These concepts of Purusha are crucial in understanding various aspects of Ayurvedic treatment, including Daiv-vyapashraya (supernatural treatment), Yukti-vyapashraya (treatment based on logic), and Satvavjaya (psychological treatment), which require a clear understanding of the different aspects of Purusha.

The discussion also touches upon Rashipurusha, which is a combination of 24 entities and gets influenced by emotional states like Raag (attachment), Dvesha (aversion), and Moha (delusion) according to Nyaya Darshan.

Overall, these concepts provide a comprehensive understanding of the Purusha in both Ayurveda and various philosophical traditions.

Prakriti- Prusha Relation:

Here’s the relationship between Prakruti and Purusha:

1.Interdependence:

- Like the lame and the blind, Prakruti and Purusha rely on each other for fulfillment. They share an interdependent relationship where each complements the other’s deficiencies.

2.Anticipation and Expectation:

- Prakruti eagerly awaits the arrival of Purusha, who is the enjoyer of the world. It anticipates the Purusha’s presence for the manifestation of all actions.

- Purusha, lacking discernment, experiences a cycle of joy and sorrow through its association with Prakruti.

3.Purpose and Collaboration:

- The collaboration between Prakruti and Purusha is driven by their mutual expectations. Prakruti provides the means for manifestation and action, while Purusha seeks liberation (kaivalya) through Prakruti’s enlightenment.

- They work together, akin to the blind carrying the lame, and the lame guiding the blind, towards their collective goals and destination.

4.Symbiotic Relationship:

- The relationship between Prakruti (Primordial Prakruti or Pradhân) and Purusha mirrors that of the blind and the lame. Prakruti, like the blind, lacks consciousness, while Purusha, like the lame, is inert.

- Just as the blind person navigates with the help of the lame, Prakruti evolves through its connection with Purusha, ultimately leading to creation.

- Similarly, just as the lame person reaches his destination with the aid of the blind, Purusha attains liberation through Prakruti’s enlightenment.

5.Shared Purpose across Darshanas:

- Other philosophical systems express similar sentiments regarding the intertwined nature of creation and liberation through the symbiotic relationship of primal forces like Prakruti and Purusha.

Prakriti- Prusha Differences:

Here are the key differences between Prakruti and Purusha :

1.Nature:

•Purusha: Chetan (sentient, conscious entity).

•Prakruti: Jada (insentient inert matter).

2.Role in Actions:

•Prakruti: Sole cause of all actions in the universe, both perceptible and hidden.

•Purusha: Actionless; merely a witness.

3.Causality:

•Purusha: Cannot be the cause of any substance or entity in the functioning of the universe.

•Prakruti: The primary cause of everything in the universe.